Regret You Didn’t Ask? 3 Steps to Finding Family Lore You’ve Lost

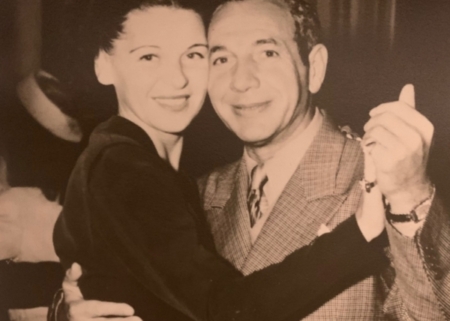

My adult son wants to know more about Papa Maxi, his great-grandfather (on my husband’s side) for which he is named. I rush to share what I know and notice I’m stumbling over my incomplete sentences. I tell him Papa Maxi was a boxer on the Lower East Side, lived the “high life” on Park Avenue, danced at the Copacabana, and attended Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz’s wedding. In response to some follow-up questions, I do a quick Google search and discover that Lucy and Desi eloped. Did I remember that wrong? Maybe Papa Maxi attended one of their elaborate anniversary parties? Now that my mother-in-law has passed away, I can’t ask her. I feel overwhelmed with grief and regret.

It wasn’t until I tried to tell my son a clear narrative about Papa Maxi that I realized I didn’t have one myself. Nearly everyone I work with, no matter how much they know about their family history, tells me they regret not asking their parents or grandparents more questions. Some lament they weren’t interested when stories were shared (like most kids and young adults), others say they listened but feel bad they didn’t write down what they heard (but who takes notes at family dinners?)

Since research has shown that developing a strong family narrative may be the single most important thing you can do for your family, here are 3 things you can do to find the family lore you fear you’ve lost.

1 – Write Down Your Questions

Please don’t dismiss this as nonsense or exclaim “What’s the point!” All is not lost and this is a critical first step on your road to discovery.

Writing down your questions helps you get clear on the information you are missing. Sometimes I get so lost on what I don’t know, that I lose sight of what I do know. When I get my questions out of my head and onto a page, I can zero in on finding the pieces of the story that matter.

Writing down questions also puts you in a better position to ask when opportunity knocks. I worked with a woman whose father had dementia. She was filled with sadness and regret for not asking more questions when she could. I suggested she write down her questions. After some grumbles about it being too late, she went home and did it anyway. As it turns out, a few weeks later she ran into an old friend of her father. After saying hello and catching up, she thought to ask him one of her questions. She learned things about her father she didn’t know and through his eyes, saw her father in a different light.

Writing down your questions is something you can do in five minutes — no really, set a timer for 5 minutes and put your pen down when time is up. It creates cognitive tension (aka the Zeigarnik Effect) and gets your subconscious brain working for you. Then, as you go about your life additional questions will surface to your conscious mind and all you need to do is capture them on your list.

2 – Make a List of People

Take 5 minutes (set your timer!) to make another list in your notebook or on your computer of anyone who might have some family information. List aunts, uncles, cousins (1st, 2nd, 3rd…), spouses, significant other(s), your siblings, and kids. Include neighbors, family friends, classmates, and co-workers. This article may have some other ideas for you. As you go about your life and other people come to mind, jot them down on your list.

When you are ready to take action, start with the person who feels easiest to contact. The first message should ask if they would be willing to speak to you about your family history. If yes, schedule a 15 minute call. Start with an easy question that’s not emotionally charged to build a rapport.

Take notes on your conversation or use a recording app — I’ve always used Rev.com for live interviews — Rev Call Recorder is for phone calls. What’s great is you can forward the audio file after your call to Rev.com and, for a reasonable price, you’ll receive a transcription of your interview in Word within 24 hours. I’ve found their accuracy to be very good, even when someone has a heavy accent. And so it’s clear, I’m receiving no compensation from Rev.com. I’m just an old-fashioned happy customer.

Family lore gets dispersed in ways that aren’t intuitive so you really don’t know what someone knows unless you ask. Reaching out to people may feel uncomfortable at first, but more often than not clients tell me with enthusiasm how worthwhile these connections and conversations have been.

3 – Do Some Research on the Internet

Search for specific information about a family member (i.e., in a birth or death certificate) or research the place or era in which the person lived (i.e., the Lower East Side in the early 1900s). Pick a question from your list and set up a Word doc on your computer to keep track of your research, noting your question at the top of the page. It’s so easy to spend hours down a rabbit hole of research and end up with nothing to show for it so be sure to copy into your Word doc not only the link for each website you visit, but the information you find (or that you found nothing so you won’t forget and go back). Writing what you find also helps you synthesize the information and make better decisions about next steps.

You can begin with this list of Jewish family history resources or the Ancestry.com Jewish family history collection, which is free. It includes Holocaust records from the USC Shoah Foundation, Eastern European records from the Miriam Weiner Routes to Roots Foundation, and records from JewishGen.

Focus on family members that you’ve known, particularly parents and grandparents, and remember that you don’t need to know everything, you just need to know a few things to make their lives meaningful to your kids.

It’s not easy to write a family narrative alone. We offer guided online experiences that help people create short and shareable narratives about their Jewish family history in a few weeks. We also provide live and online Storykeeping programs to synagogues, family groups, non-profits, and other organizations. Find out more here.

Please Share Your Comments